Before openly turning violent in 2009/2010, the “Ahl al-Sunnah wa al-Jama’a ‘ala Minhaj al-Salaf” (later renamed “Jam’atu Ahl al-Sunnah li al-Da’wah wa al-Jihad”), popularly referred to as “Boko Haram” (BH), had (as its various religious names suggest) a well-developed ideology that was supported by numerous arguments or narratives used in its recruitment of members. The ideology was sufficiently infused with mainstream teachings about Islam related to creed, symbolisms and worship to make it identifiable as an Islamic organization. It however had some unique extremist combinations of teachings and concepts that gave it a distinctive identity and exclusivist ideology of its own and which distinguished it from and made it hostile towards all other Islamic groups and movements in Nigeria at least.

Framing of Grievances with a Religious Ideology

The various socio-economic and political grievances faced by the majority of people of various faiths and ethnicities in North Eastern Nigeria are not unique to the region or to Nigeria. However, “grievance without an ideology creates no movement”. What is unique to the Boko Haram (BH) was the particular religious ideological interpretation of the grievances and the framing of their only acceptable solution to the challenges that were proposed by the BH ideologues and leadership. The grievances related to various forms of corruption at every level of society (political marginalization and thuggery, economic exploitation by the leadership and elite, endemic poverty, breakdown to the justice system and poor education, breakdown of social values and morality, etc.) were interpreted as evidence of the failure of secular democratic system of development and societal progress, and proof of what happens in the absence of the sacred. The solutions to all these societal challenges are presented and framed as “Islamic” as defined and interpreted by the BH ideologues, intellectual leadership and recruiters.

Many Nigerians (both Muslims and Christians) have been disillusioned by the exceptionally corrupt and abused political and economic system of the country and region, particularly at the grassroots level. The BH group did not believe in the legitimacy or the ability of the existing democratic structures or legal system to change the situation. They also did not believe that any peaceful or non-violent methods of changing the status quo to their version of an “Islamic State” would be tolerated by the current leadership or the international community. The very brutal crackdown by the Nigeria Security Services against the group, but also against many other innocent citizens in 2009 and thereafter, made it even clearer to the group that the state was not just “evil” (taghut) but against Islam in general and them in particular. The group was fully convinced that no peaceful end to societal problems and their grievances was possible and that their violent ideology was all along the only hope for dealing with their now many greater grievances. The group had developed and borrowed many arguments and religiously framed justification for their violent means and ends from other “jihadist” or violent extremist groups. Some of the arguments they used however were picked from fringe or extreme positions on specific issues that were held by some otherwise non-violent mainstream scholars and groups.

Escalation of Violence and non-Religious Recruits

With the escalation of violence by both the Joint Task Force (JTF) and the now vengeful Boko Haram (BH) under its new ruthless leadership (of Abubakar Shekau), the weakness of the State and its inability to keep law and order became more obvious. Many others, (and eventually the majority of ‘members’) joined the BH movement, but for various other reasons that had little or nothing to do with the religious ideology of the group’s intellectual leadership and ideologues. Many of these new recruits saw themselves and their families as victims of the abuses and brutality of the State Security Services and their civilian informants. Others however were opportunists who took advantage of the crisis for their own criminal exploits. Yet, others have joined the conflict for combination of many other reasons.

At the core and epicentre of this group however, the leadership of the BH movement, its ideologues and its recruiters remained loyal to the promotion of their religious ideology and agenda, and to the recruitment of religious and not so religious members and sympathizers or supporters.

The Appeal to Religion

The appeal of the religious ideology of BH comes from the ability of the ideologues and recruiters to frame the otherwise mundane socio-economic and political frustration and grievances as being the result of an anti-religious and un-Islamic secular and systematically oppressive democratic system and values; and then supporting this link with religious texts and arguments.

The religious appeal of the BH ideology also comes from the many arguments and narratives quoting religious text and figures that are used to promote a more just, equitable and godly alternative system as defined by themselves, even if through violent means.

Violent extremist ideologues are also able to use “religious” arguments to justify any means of achieving their ends – i.e. instrumentalizing of religious texts and concepts.

Religious texts, interpretations, concepts and teachings are usually all seen as divine and sacred by most followers. The use and clever manipulation and re-interpretation of religious text and the use of “religious” arguments by BH and other extremist groups to justify their ends and brutal means also help give an aura of sacredness, immunity and divine authority to their arguments. This has made it difficult for lay people or non-specialist scholars to critique or deconstruct extremist narrations as most people (Muslims) are functionally illiterate in such matters as Islamic jurisprudence and legal theory and are very often ‘paralyzed’ or disarmed by religious texts and arguments. The effect of such religious framing of extremist arguments is that they are often more successful in getting the more naïve and devout to suspend sound critical thinking and ‘oppress’ their common sense.

Concerns over Consequences of an Unchecked BH Ideology

BH recruiters and currently quiet supporters of the BH ideology continue to attract and recruit members and supporters to their unique form of Islamic “Liberation Theology” from across the Sahel region. A very few of these are ready to become violent. Those that do are usually eventually either imprisoned or killed. The remaining non-violent members find other ways of supporting their cause and undermining the State, safety and security. Others focus on challenging any Islamic/religious support for democratic values and processes, conventional education (“Boko”), interfaith bridge-building and peaceful coexistence, and non-violent means of societal reform or civil action, etc.

As the most violent phase of the religious and non-religiously inspired members of BH appears to be coming to an end, there is deep concern that if the religious arguments and narratives used to justify and support the BH ideology are not effectively countered and deconstructed by alternative and more authoritative religious narratives, the movement in various forms and mutation will probably continue to attract new members, some of whom will be violent. This will continue to sustain some level of insecurity and violence in North Eastern Nigeria and beyond.

The freedom of speech and of expression inadvertently also protect the recruitment activities of BH and the public sharing of their literature and social media content. It should therefore be expected that if the BH ideology and its supporting arguments are not refuted effectively and decisively across the region, the challenges ahead of societies where such groups operate will continue to increase.

The Limits of Governments

It is very unlikely that any government in the very near future will be able to effectively deal with the various socio-economic and political grievances that BH members and sympathizers have against the State, and which are used with the support of their ideology in the recruitment process.

This means that for those who will continue to have various grievances against the State or society there is a ready-made religiously attractive (albeit extremist) ideology to explain the cause of their grievances and to offer an alternative “religious” (albeit-violent and utopian) solution.

Without effectively countering the ideology of BH and its supporting arguments, the existence and persistence of grievances will continue to act as a motive for BH recruiters and ideologues to continue to propagate and sustain their ideology.

The Government also does not have the competence nor the legitimacy (in the eyes of BH sympathizers and even most religious citizens) to effectively counter and deconstruct the narratives and arguments developed by various extremist groups to build and support their violent ideology. In many cases, government is actually viewed as a corrupt perpetrator of structural violence.

In addition, the government also lacks the credible network of local grassroots organizations and activists that are eager to use and disseminate resources and knowledge that can help them effectively challenge the ‘distorted’, ‘misguided’, ‘heretical’ and ‘strange’ arguments of violent extremists, while building greater community resilience through both faith-based critical thinking tools and the collaboration of various stakeholders.

The Evolutionary Path to Violent Extremism

Before becoming radicalized, most people pass through a series of evolutionary stages or phases. The first step is usually simple curiosity for answers about extremism and violent extremism, followed by greater interest and preoccupation with learning and discussions on the subject matter; next comes gradual acceptance of the validity of some of the arguments (but not all or most) then conversion to “their side” and passive support for/defence of their positions; this is followed by actively promoting the ideology and narratives or recruiting followers. The final stage may be one where violent action is taken.

Alternative narratives should be designed to repeat the evolutionary process, or go back a step at least, but with a different trajectory. Alternative narratives should therefore also be designed to encourage debate and discussion, to revive curiosity in the heart and minds of those who have taken the extremist’s narrative as true, and to pose critical open-ended questions that may assist the extremist in sincerely re-assessing evidence and assumptions.

Those who are far “up” the evolutionary process of radicalization may naturally be the most difficult to convince. They would likely use opportunities for discussion as means of promoting, defending and reinforcing their position even further. While hope for them is not lost, (history has shown that brutal persecutors can be converted) the most important target should be those who are not yet fully radicalized because they are more likely to be open minded and objective. In engaging such people, it might be useful to debunk misinformation and suggest alternative interpretations of texts and current affairs, especially in light of the fact that many violent extremists have not given sufficient thought to the accuracy of the ideology and narratives they have bought into.

Religious Gate-Keepers and Building Community Resilience

To effectively build resilience against any form of violent extremist ideologies within the community, it is essential that quality and effective counter arguments and alternative narratives are made available and accessible to youth and community leaders, teachers, parents, students, preachers, religious leaders and other institutions (such as prisons) which deal in various ways with violent extremism.

Most societies however have their formal and informal religious community gatekeepers and institution that can facilitate, hinder or undermine the flow of new religious knowledge and information – including counter-narratives. Their endorsement and support of literatures and other learning resources is important for wider acceptance and dissemination of material for Preventing Violent Extremism (PVE). It is also therefore important that the community of gatekeepers are approached first before reaching out to the wider community of youths and others through social and public media channels.

After the dissemination of relevant books (and audiobooks), it will then be easier for social and public media to disseminate the content of books through various other formats. Minimum confusion or hindrance to the role of public and social media will be expected only AFTER the enlightening of religious community gatekeepers. Failure to deal first with gatekeepers and win their support can be a major challenge to the role and success of various other media activities in PVE work that focuses more specifically on any interpretations of religious texts.

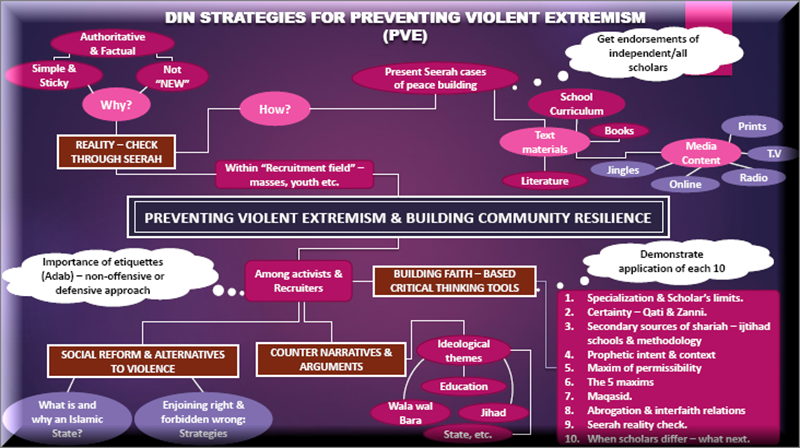

DIN PVE Strategies

DIN and Resource Development

This involves carrying out surveys to find out the narratives that BH recruiters and other violent extremist groups use to draw people into their fold; and then develop counter-offer or alternative narratives to the recruitment field.

The Research Department of the Da’wah Institute of Nigeria (DIN), under the Islamic Education Trust (IET) based in Minna has surveyed, classified and analyzed over 200 narratives and arguments that have been used by BH and other violent extremist Muslim groups from other countries.

These arguments have been classified by the DIN into 4 major themes or groups:

- Those related to the discouragement or prohibition of modern conventional education (‘boko’);

- Those used to dehumanize others and undermine peaceful interfaith relations;

- Those used to justify rebellion, violence and aggression against non-hostile others in the name of jihad;

- Those calling for compulsory Muslim migration (hijrah) and the establishment of an “Islamic State” or Caliphate.

While there are a few other issues that violent extremists argue about, the above broad categories are in the assessment of DIN, the most important to counter.

As the ideology behind violent extremism can result in numerous narratives to suit various contexts, it is worth focusing significant attention on countering the foundation of the ideology and roots of the narratives instead of just targeting the endless ever-changing and evolving narratives; although, both the ideology and the narratives need to be addressed. It is also important to address the various push and pull factors that are behind violent extremism and offer alternatives (“counter offers”) to violent means.

Ideological challenges and counter narratives should be designed to drain the intellectual recruitment capacity. This makes it difficult for such groups to recruit intelligent and charismatic leadership that can sustain and defend the ideology from external or internal challenges. Without intellectual and religious credibility, unity, cohesion and effective succession by sincere, convinced and committed followership is practically impossible.

The DIN has a team of competent researchers and a supporting network of religious scholars and activists who have had over two decades of experience responding to extremist arguments such as those used by BH. This network of intellectuals and grassroots activists have helped in developing and reviewing the faith-based ideological responses, counter and alternative narratives developed by the DIN. The final counter/alternative narratives developed by the DIN are further reviewed and endorsed by another set of more than 30 respected scholars, Imams, religious leaders and academicians mainly from the region.

Six major books (and training manuals) have been developed by the DIN to offer alternative narratives to the narratives that form the major pillars of the BH ideology.

The 6 titles are:

- Shari’ah Intelligence: The Basic Principles and Objectives of Islamic Jurisprudence.

- Is ‘Boko’ Haram? Responses to 35 Common Religious Arguments against Conventional “Western” Education

- Relations with Non-Muslims: Association, Disassociation, Kindness, Justice and Compassion

- Jihad in Islam: Its Use and Abuse among Muslims.

- Muslim Residence and Hijrah: What Makes a State “Islamic” Enough?!

- Building Resilience against Intra-faith and Inter-faith Extremism: Lessons from the life of Prophet Muhammad.

The first and last title are not direct counters to any of the four major pillars. The first is meant to be an intellectual vaccination that would help people to easily identify defective arguments; while the last is a compilation of cases from the prophetic history (Seerah) of proactive interfaith peace and relationship building. These serve as authoritative memorable counter narratives to all four themes and are also a multipurpose set of critical thinking tools.

The Need for Training

After the development of credible and effective alternative narratives, there is the important need of training of multiple “voices” that would effectively deliver the messages towards PVE/CVE. Imams, muftis, Islamic studies teachers and lecturers, da’wah activists and others who are actively involved with engaging with the populace on a regular basis have a vital role to play in PVE/CVE.

On the ideological spectrum, the violent extremist is closer to the Salafi than to the Tariqa or Sufi groups among Muslims. A person who is dissatisfied with the protocols and opinions of many of the Tariqa movements will probably become a Salafi before declaring independence of Salafi scholars and become a violent extremist (or “Salafi Jihadist”). The Salafi scholar or a Salafi organization is therefore most probably the most trusted scholar or institution in the eyes of the violent extremist.

Consequently, the most authoritative counter narratives would have to be developed, presented and argued, not by a Tariqa Scholar, but by a Salafi who is closer to understanding the paradigm, heart and mind of the violent extremist. Better still, a former respected “Salafi Jihadist” recruiter who was regarded as knowledgeable by his former colleagues. It goes without saying that counter narratives developed or presented by non-Muslims or Muslims who are viewed as “modernists” or “secular Muslims” also would be out of the questions!

Even among Salafis, individuals with “street credentials” are most effective in carrying counter narratives. They are people who have spent time with the target audience and have known them personally.

This however does not mean that only Salafi scholars are qualified to engage in PVE/CVE work. This is because many of the concepts and ideas that make up the extremist ideology can be found within the teachings of a number of Muslims groups, movements and sects, they each do not necessarily produce violent extremists. Each one or two or more of these beliefs which may be found within a particular individual or mainstream group of Muslims has not been sufficient to result in violent extremism. This is because of the existence within each of these mainstream groups, certain other beliefs and structures that serve as ideological checks and balances against violent extremism. On their own, therefore each of these beliefs does not necessarily produce violent extremism, though they are in certain contexts, important ingredients. In a unique combination however, the synergy of these ideas along with the required grievances, means and charismatic leadership, can easily create, however distorted, perverted, deviant or heretical, a “religiously motivated” ideology for violent extremism.

Therefore, countering the narratives of violent extremists will necessarily involve countering some of the commonly held narratives of non-violent groups, but which violent extremists take a few steps further. Hence, the need for scholars from other mainstream groups have a significant role to play in PVE/CVE.

Trust is the most important currency in countering violent extremism (CVE) and in the credibility of counter narratives. CVE therefore moves at the speed of trust. The success of a counter narrative is based largely on the trustworthiness of its source, its veracity and soundness, the extent of its distance from ulterior motives and its independence of some ‘other’ authority. The more independent of government a scholar is believed to be, the more credible he (or she) is likely to be in the eyes of most youth.

It is very important for these scholars and activists to be imbued with necessary skills to effectively tackle the ideological challenge of extremism. Most of the scholars who are best qualified to counter the narratives of violent extremists are unfortunately unable to operate on social media platforms due to computer illiteracy. There is the need therefore to train such scholars in the use of modern technology both for assessing and for disseminating information.

Also, such scholars need to be grounded in the juristic fields/subjects of Usul al-Fiqh (Principles of Islamic Jurisprudence), Qawa’id al-Fiqhiyyah (Islamic Legal Maxims), and Maqasid al-Shari’ah (Hiigher Objectives of the Islamic Law). This gives them the critical thinking tools for scholarly Islamic-oriented PVE/CVE work and deconstructing violent extremist arguments.

Similarly, such speakers need to offer alternative ways of dealing with the various push and pull factors that are realistic and creative. This calls for training on the necessary managerial tools for the effective utilization of the various human, financial, and physical resources at their disposal for improved da’wah services.

Muhammad Yusuf (founder of “Boko Haram”) was a recruiter par excellence! Many scholars who knew him very well insisted that he was not very knowledgeable about Islam, but that he did have charisma and the ability to touch and move a crowd in spite of his limited understanding of Islam and the world. Charismatic leaders of any age are potentially powerful recruiters within the “recruitment field” of the general population of Muslims.

Therefore, those involved in presenting alternative narratives need to have both charisma and sincere empathy to the humanity of the target audience. “What comes from the heart goes to the heart!”

The Need for Multimedia Dissemination

Some violent extremist organizations have gradually developed some of the most sophisticated high quality visualized messaging systems targeting the minds of modern Muslim youths for both social and mainstream media. Though 80% of their output is in Arabic, they compete in quality and impact with the best advertising agencies in the world in their “solution-focused” marketing and branding of themselves. Understanding their system and how to counter it will go a long way in countering the next social media recruiting methods of these and any future extremist groups. Their hijacking of mainstream media has helped them to incite greater Islamophobia against peaceful mainstream Muslims everywhere, and in the West in particular, with the anticipation that this will contribute to the frustration, polarization and social marginalization, and eventual radicalization of more Muslim youth who could then be more easily recruited.

Therefore, there is the urgent need to proactively take back the stage in re-presenting Islam to the masses and countering the narratives of violent extremist. This would be done through audiobooks, radio presentations, television programming, short videos, internet and the social media.

The Need for Books

From surveys conducted by the DIN and a few other organizations, the most important medium of disseminating religious knowledge and information to Imams and most other religious community gatekeepers is through literature especially books, and not from online sources (yet). Books still account for over 90% of their learning resources of religious information.

The other advantage of books over some other methods of disseminating alternative or counter-narratives it that they are safer for people to deliver and more “quiet”, unlike sermons and talks that may put the speaker/presenter at risk of becoming a target of BH. It is therefore easier to get greater community penetration and cooperation than through many other means of communication.

Similarly, the teaching of Islam and the Islamic Studies curriculum and textbooks in schools and various classes by various organizations and institutions should have more “maqasid” or values-oriented content and perspectives. They should include in some reasonable depth, a good basic introduction to the Principles and Objectives of Islamic Jurisprudence (Usul al-Fiqh and Maqasid al-Shari’ah) and key episodes in the Prophetic History (Seerah) by a competent teacher. This would help students and youths to develop the critical thinking tools that would serve as an effective “intellectual vaccination” that will build resilience and immunity against many extreme ideologies and the hijacking of the religious narrative of mainstream Islam.

(A very useful educational resource in a similar vein to the above is the paper, Living Islam with Purpose by Sheikh Dr. Umar Faruq Abd-Allah of the Nawawi Foundation, USA, available online).

Challenges with Measuring Impact of PVE Activities

Countering the religious ideology of violent extremists, building community resilience and “immunity” against the arguments or narratives used by extremist recruiters, are related more to religious education for social work, peace-building and Preventing Violent Extremism (PVE), than to the more specialized work of Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) or counter-terrorism. In contrast to CVE which is usually by security services, Preventing Violent Extremism (PVE) is the ongoing work to change the course of an individual’s actions before that individual becomes radicalized or engage in violence. PVE initiatives share a common characteristic and challenge: they are intended to eliminate something before it occurs. This means the object of PVE work is often difficult to identify and the success of such work is nearly impossible to measure. So, while measuring CVE is similar to measuring the effectiveness of a doctor’s prescription, measuring the effectiveness or impact of PVE is similar to measuring the effectiveness of better environmental sanitation, health education and nutrition.

Confusing PVE with CVE encourages the misconception that all work aimed at eliminating or reducing violent extremism is highly specific – a niche field concerned with specialized activities such as deradicalization of fundamentalists, border security, vetting processes, and other targeted strategies. This is perhaps one of the most damaging misconceptions for the growth and promotion of sustainable and effective PVE in general, and especially for religious education that deals with deconstructing extremist ideologies and paradigms.

Having said this, it should be borne in mind that violent religious or ideological extremism is not new to Islam (or to any other of the major world religions). The unmatched effectiveness and successes of competent mainstream Muslim scholars in deconstructing the arguments and narratives of violent extremists and preventing their ideologies from growing and spreading in the past has been well recorded and repeated by scholars of Islamic theology and history. In recent times, tremendous success has been recorded in the works of such competent and respected traditional Muslim scholars working on violent extremists in prisons in especially Mauritania and Libya. This shows that even though it is difficult to measure, success has been recorded in this approach to countering the ideology of violent extremists though better religious education by competent and credible religious authorities.

What we can assume however, is that there is no silver bullet – that the holistic work of PVE is the incremental work of engaging, supporting, and encouraging individuals so that they are better equipped to interact with their world in positive ways. Quantifying this effectiveness is a unique challenge to PVE work. Prevention of violent extremism is a campaign for better education, citizenship, justice, equality, peace-building and tolerance whose successes are nearly impossible to measure accurately, at least in the short and medium term.

BRIEF OVERVIEW ABOUT EACH OF THE 6 TITLES

1. Shari’ah Intelligence: The Basic Principles and Objectives of Islamic Jurisprudence

This book is a carefully developed and purpose-driven introduction to the principles of Islamic jurisprudence (Usul al-Fiqh), legal philosophy, and the higher intents and purposes of Islam (Maqasid al-Shari’ah). This gives all the critical thinking tools for scholarly Islamic-oriented PVE/CVE work and deconstructing violent extremist arguments. These “critical thinking tools” and concepts have helped scholars respond to social realities and the various arguments and methods used by religious extremists throughout Islamic history. Scholars have also used them to ensure that orthodox methods of interpretation of texts and contexts have limited the extent to which the mainstream schools of jurisprudence can run wild or go rogue on its own values.

It is like giving the formula for finding the volume of a cylinder, or being taught “BODMAS” for dealing systematically with mathematical problem solving. It allows people to see where the construction of the extremist’s narrative went wrong in its structure and how to correct it using agreed equations of Islamic jurisprudence. Without a sufficient grounding in Shari’ah Intelligence, many get paralyzed by the diversity of opinions held by various scholars or by someone saying “but that some great scholar also said such and such (extremist view)” or “but we must respect all views by other scholars”, even where such views are damaging to human life and peace. Because the rules of interpretation of text in response to context are well established by all the major schools, it is easy once these are known for anyone to know HOW to show the weakness in the methods and conclusions of violent extremists, and HOW to present ALTERNATIVE interpretations, narratives and conclusions (of texts used by extremists) that are more in tune with the position of the majority of classical or contemporary jurists who do not accept the positions of violent extremists.

This equips people with better conceptual tools obtained from within the Islamic tradition that allow them to more easily identify and systematically critique extremist, unjust, irrational and harmful opinions (fatwas) associated to interfaith relations with non-Muslims, women’s rights, contemporary application of Islamic law, minority rights and a host of other issues.

2. “Is ‘Boko’ Haram? Responses to 35 Common Religious Arguments Against Conventional “Western” Education”

This book deals with the core arguments used by Boko Haram (BH) to justify one of their major ideological positions which distinguishes them from most Muslims and jihadist groups – the condemnation of conventional education as religiously prohibited (haram). It is from their arguments on this theme/issue that they acquired the name “Boko Haram”.

The arguments against conventional modern or “Western” education were used to not just condemn such an educational system, but to also condemn students, teachers and all those who supported such institutions. These arguments eventually became part of what justified the bombing and destruction of schools, which also led to the closure of most public schools in the areas that came under BH control.

Most of these arguments are however not new nor are they all unique to BH, though only BH went as far as using them along with others to justify violence.

Most of the arguments used by BH to justify their condemnation of Western or secular education were originally used by local preacher and scholars to counter the earlier attempts by Christian missionaries during the colonial and early post-colonial period to Christianize Muslim children. And while that strategy of Christianising Muslims through the educational system no longer hold true, the arguments are still in circulation among many at the grassroots level. These arguments are widespread and continue to be used to prohibit or at least discourage many Northern Muslim parents from sending their children to conventional schools or supporting their children’s education.

The religious and ‘logical’ framing of these arguments have continued to make them believable among many of the uneducated, which has in turn prevented many from the opportunities for social and economic progress that usually follows better educational standards.

The Boko Haram group has used these arguments to give credibility to themselves and to also undermine the Islamic credentials and qualifications of those Muslim scholars who would oppose them from among university graduates and lecturers, even if such Muslim scholars had specialised in Islamic Studies or Islamic law.

Popularising the weakness and baseless assumptions behind these arguments helps is not just countering recruitment efforts of BH ideologues, but also undermining their supposedly religious and scholarly credentials.

Arming religious community gatekeepers with this information will also help in building resilience against various forms of extremism, but also strengthens religious and community leaders with arguments to support and promote better educational standards within their communities and better collaboration with various stakeholders.

3. “Relations with Non-Muslims: Association, Disassociation, Kindness, Justice and Compassion…”

This book is a compendium of over 45 of the most common “faith-based” arguments used by various shades of Muslim extremists, including violent extremist to justify interfaith “bridge-burning”, hostility and the breakdown or disintegration of community relations between Muslim and people of other faiths.

The arguments are also used to counter the activities of community peace builders, conflict mediators, promoters of interfaith engagement and cooperation.

While many of these arguments have been used to only sustain “negative peace” (or absence of conflict), they have become obstacles in bridge-building efforts where “positive peace” and reconciliation are critical to long term peaceful coexistence.

These religious arguments have also been used by extremists as part of their arsenal in supporting their ideology of hatred towards people of other faith and towards Muslims involved in interfaith bridge-building.

Extremists have used these arguments to smear the reputation and question the religion credentials and authority of those Muslims involved in interfaith peace-building. Such Muslims have been named with various derogatory qualifications as “lax”, “liberal”, “secular”, “western”, “hypocritical” or “sell-outs”.

This book counters these various arguments using the highest authorities – the Qur’an, the actual practises of Prophet Muhammad (p) and his companions along with the opinions of some of the most respected early and medieval Muslim scholars and jurists.

Equipping Muslim community gatekeepers and religious speakers with these responses to the extremist arguments, helps build the resilience against recruitment strategies of violent extremists. These responses also give greater validity and confidence to the religious legitimacy of community peace building and interfaith dialogue and engagement efforts of those involved. These responses and counter/alternative narratives also add to the arsenal for preventing violent extremism, and building community resilience.

4. “Jihad in Islam: It Use and Abuse by Muslims”

This book is a compilation of scholarly responses to the various misuses and abuses of the concept of “Jihad” in Islamic jurisprudence. It focuses on responding to all the major arguments used by violent extremists to justify their violence and acts of terrorism in the name of Islam.

While some arguments used by extremists have been used or supported by some Muslim jurists of the past, none of these interpretations have the support of the actual lived practices of the Prophet Muhammad or his respected Rightly Guided Companions and successors. It has therefore become necessary to look more carefully and analytically at each and every text used by violent extremists today, to interpret it in its own proper context without dismissing or contradicting other relevant texts or the clear and explicit values and higher purposes (maqasid) of Shari’ah (or “Islamic law”) as agreed upon by the consensus of Muslim jurists through the ages.

Most of the texts used by violent extremists are either taken completely out of their original contexts or interpreted without due consideration of other relevant texts.

The text-by-text, issue-by-issue style of the book make it easy to identify specific texts and arguments with their accompanying responses. This makes the book an easy-to-use resource for Imams and other religious community gatekeepers for countering each of the specific texts and arguments used by violent extremists.

It also serves to sow doubt in the absoluteness and certainty with which extremists handle the interpretation of texts that could result in serious consequences of life and death. And while the traditional Islamic ethics and etiquettes of disagreement are important in most issues where respectable scholarly disagreement is seen as healthy diversity, the book is very categorical on those issues where diversity of opinions has been exploited by some of justify acts that even the scholars they purport to quote would never support.

The book therefore serve as an easy-to-use, well-reasoned and referenced compendium of responses against religious arguments used to justify unprovoked hostility and aggression against others (Muslims or otherwise). Even where the legitimate use of force or arms may be justified in Islamic law, the book vehemently argues against absolutely any religious justification for terrorism or the killing of innocent civilians and non-combatants which have been a common practise of groups such as BH.

5. “Muslim Residence and Hijrah: What Makes a State ‘Islamic’ Enough?”

Contrary to the beliefs of many violent Muslim extremists, Muslims have always had a sizeable proportion of their population living as minorities under non-Muslim rule from the earliest days of Islam at the time of the Prophet Muhammad and throughout Islamic history. Muslim scholars through the ages have also analysed the various criteria that must be met before it becomes recommended or compulsory for Muslims to migrate or change their residence from one place to another. As a rule, unless Muslims are being persecuted or denied the freedom of religion they had to respect their social contracts as law abiding citizens.

This book responds to all the major arguments used by various extremist groups to justify belligerence and violence against non-Muslim states or communities, and against Muslim States that do not subscribe to their model of an “Islamic” state. The book also responds to the arguments of those who do not see a compatibility between democracy, democratic values and Islam, and whose only alternatives for political reform would involve some degree of violence.

The book argues that the system espoused by jihadist movements, the “Caliph system”[1] is only one among various other islamically legitimate and evolving structures or forms of governance that Muslims could adopt or adapt for themselves.

In a text-by-text and topic-by-topic approach the book also responds to all the common texts and arguments used by violent extremists to push forward with their violent agendas that have cost thousands of Muslim lives and which have done more to undermine the higher intents (maqasid) of Islam than anything done by even non-Muslim enemies of Islam in recent history.

As many of these arguments are new to many Muslim leaders and even local scholars, the book serves as an easy-to-use guide for responding to groups calling for civil unrest, insurgency and violence using pseudo-religious arguments with “textual evidence”.

This book is therefore critical in any holistic approach to building community resilience against recruiters and in preventing violent extremism.

6. “Building Resilience against Intra-faith and Inter-faith Extremism: Lessons from the life of Prophet Muhammad”

This book presents about 30 historically authentic and powerful cases of various peace-building episodes in the life of Prophet Muhammad in his relations with various communities and individuals of other faiths.

As these are actual historical cases of what really took place during the life of Prophet Muhammad, they have near universal acceptance by Muslims of all sects and tendencies, and are among the hardest arguments to counter; they are explicit in the lessons they teach about interfaith relationship building with fairness, compassion, forgiveness and magnanimity.

These real-life cases are also in need of very little (if at all) interpretation or scholarly analysis, and are therefore easy to understand and share with others.

The fact that these are all narratives in form of stories also makes them “sticky” and easy to remember for youth and less intellectually inclined majority of Muslims.

From surveys conducted by the DIN, these cases from the lifetime of the Prophet Muhammad have been among the most effective and easy-to-use counter narratives used by lay persons with minimum religious education literacy.

For scholars and religious community gatekeepers, these undisputed historical cases and episodes have been identified as powerful yet simple supporting argument for numerous other counter narratives and responses to extremist positions. The cases presented in this book may easily and authoritatively highlight the contrast between the civility, pro-active peace building tradition at the heart of Islamic teachings as lived by the Prophet Muhammad with the hostile, harsh and inhumane teachings of violent extremists.

While presenting each of the well-referenced historical cases in the biography of Prophet Muhammad (Seerah), the book also cites numerous supporting texts from the Qur’an and hadith. It also cites supporting statements of respected classical scholars about the implications of those historical episodes in the everyday lives of Muslims.

The lessons and implications of each of the cases presented in this book counters nearly all the arguments used by violent extremists to justify hostility and aggression towards people of various other faiths including Jews, Christians and pagans.

CONCLUSION

Most violent extremists are not intellectually oriented and do not know or even properly understand each or all of the arguments that make up the pillars of the BH ideology. But many extremists know some of them on a basic level as a source of religious support for their policies and missions.

The effects of violent extremism is borne by all, as such, all hands must be on deck in order to tackle this challenge. It is obvious that the government cannot do it alone, hence, everyone has a part to play in confronting the menace.

The development and deployment of well-crafted narratives is critical to the success and recruitment strategies of violent extremists. Therefore, there is need for mass dissemination of counter-offers or alternative narrative among the recruitment field (the masses), to serve as intellectual vaccination against the extremists’ narrative. The training of Imams, teachers, activists, da’wah workers and others who are actively involved with engaging with the populace on a regular basis; as well as multimedia dissemination of resources in various formats will definitely go a long way help to build resilience in individuals and communities against violent extremism.

[1] This takes the administrative structure of the early Caliphs such as Abubakr and Umar.